|

For some people, data is a four-letter word they would rather not hear at any point in any conversation. It means looking at numbers, test scores, and comparisons. It means seeing and hearing all that is going wrong and being asked about a plan for improvement. “Data-driven” has become a reference to using statistics and testable data points to make all kinds of decisions – who gets into honors or AP levels, who can take a specific math or science course, who gets extra help, who gets extra homework, who gets… The list can go on and on. However, I hope the majority of people realize the importance of using data as more than just numbers, spotlights of weaknesses, and prerequisites for placement.

If you are in the first group of “data despisers”, how about we start to look at data simply as details about students or, as alluded to above, pieces to a puzzle? And how about we leave the negative view of data at the door and look at data in a positive light by focusing on the strengths our students have to offer? Rather than looking for weaknesses, research points out the impact of looking at people’s strengths. Did you know that people who use their strengths are three times as likely to report having an excellent quality of life? Also, check this out:

Teams who receive strengths feedback:

Now, if focusing on the strengths of an employee in the workplace can do all of that, imagine the impact of focusing on the strengths of each student in our schools. In a society where school is a safe haven and the only reliable place to be for some kids, what kind of impact could that have? What if we use the data we have to identify students’ strengths in order to completely change the path of someone’s life for the better? What if, instead of highlighting only the data that uses numbers and SASIDs, we use other data to:

Now, let’s go back to the research above one more time. What if we applied this same approach of focusing on the strengths and providing areas for stretching and growth for the ADULTS in our schools? Mind. Blown. Right? What if, instead of highlighting the data that uses numbers and test scores, we use other data to:

Instead of being “data-driven”, can we agree to be “learner-driven” and build our classrooms and schools around the learners, and the teacher-learners, inside them? As George Couros states, “The most important research we can do as educators will always be to know the learners we serve”. Instead of looking at deficits, let’s work harder to know our students and staff and use a strengths-based approach to creating change. A number, grade, or test score can give a glimpse, but there are so many more pieces to the beautiful puzzle of each individual. Let’s make it our job to put it all together.

1 Comment

I read a Neil Barrington Quote this week while researching enhancing school culture, and it hit me. It read "The Grass is Greener Where You Water It." For someone passionate about collaboration and school culture, it hit me that to build a strong community, you have to value and take care of the people IN THE COMMUNITY. When a school creates a positive school culture, it enhances the presence of opportunities for shared leadership, educator ownership, and sharing of instructional and pedagogical ideas. This article provides strategies to move to a collaborative culture. When a school creates a positive culture, it enhances opportunities for shared leadership, educator ownership, and collaboration on instructional and pedagogical ideas. However, when the word "collaboration" is spoken in a school, it is not always welcomed with open arms. Educators or leaders who have had success or are comfortable working solo may feel they are being infringed upon or that their ideas are being trespassed. However, when your school community respects each other and acknowledges individual skills and participation, all staff can move forward in a positive environment while also becoming learners. In addition, effective collaboration provides teachers opportunities for improved practices through increased leadership opportunities and a feeling of being valued in a school environment. Have a great fall, and keep striving to create a welcoming and healthy school community. The grass is NOT greener on the "other side"; it is greener where you take care of it. Building a collaborative culture will have a lasting positive effect on your school or district of learners and leaders.

Emotional wellness is an area our society is, thankfully, working to build awareness and progress. In schools it is often called “SEL” or social emotional learning and it is sometimes the focus of “self care” content in popular media. Emotional wellness refers to our ability to notice, name, work through, and then reflect on our emotions. Are there situations, relationships, or behaviors that correlate with certain emotions? When our emotions are most intense, are we able to manage our behaviors and words in a way that is both authentic to ourselves and respectful to others? We should be able to answer these questions for negative, positive, and every emotion in between. As you read in the first three articles in this series – What is Digital Wellness?, Digital Wellness is Physical Wellness, and Digital Wellness is Cognitive Wellness – I am exploring how our use of digital media, tools, and devices can impact our overall well-being in positive and potentially negative ways. This post will look at how our use of screens, apps, and other tech tools affects our emotional wellness. Identity and Self-Expression Educators and parents who care for adolescents can agree that we want them to find their place in this world and share their gifts in a way that helps them experience a sense of purpose and belonging. When reviewing the research, the overwhelming conclusion is, “youth use social media in the service of critical adolescent developmental tasks, such as identity development, aspirational development, and peer engagement.” So, the popular mantra that is repeated among adults insinuating that teens and tweens only lose themselves in social media is actually an inaccurate sentiment. Our children still need to engage in physically and cognitively engaging activities like sports, arts, and academics while in in-person environments. However, the American Academy of Pediatrics reports that social media use is associated with “increased self-esteem, increased social capital (resources accessed through one’s social relationships), safe identity exploration, social support, and more opportunity for self-disclosure. These processes are all critical to healthy growth and identity development.” Some questions to ask the adolescents in your life include:

In both of these examples, there was much written about correlation while causation was only theorized. This is disappointing because causation is most important to help us take preventative action and promote emotional wellness for our children. While Twenge and Netflix published for popular consumption, the empirical data from longitudinal studies like this one and this one continue to show that causation moves in the other direction. After following teens over years these studies showed that symptoms of anxiety and depression predicted increased social media use, and not the other way around. What does this mean when we want to support our adolescents? It means that an increase in social media use may be a sign that we should offer help, rather than a sign that we should come down hard on the social media use itself. If your adolescents are spending more time on social media, or even just alone in their rooms with their screen devices, our first instinct should be to ask how they are doing:

Next Steps There is so much more research and many more strategies to help ourselves and our adolescents grow in emotional wellness while using digital platforms and devices. Start by using the strategies I’ve shared here in conversation with the adolescents you care for, whether it is in a classroom or at home. You will get to know them and their online spaces better through these interactions. In turn they will see that you are interested in their emotional well-being. I’m looking forward to seeing you back here soon. Our final Digital Wellness post will tackle our relationships with family, friends, and communities with Community Wellness. Check out other articles in this series: What is Digital Wellness, Physical Wellness, and Cognitive Wellness.

Cognitive wellness refers to our overall ability to think, problem-solve, and create. We actually have the power to improve our brain’s ability to acquire, understand, and apply information. But sometimes our screen use can get in the way. As you read in the first two articles of this series – What is Digital Wellness? and Digital Wellness is Physical Wellness – I am exploring how our use of digital media, tools, and devices can impact our overall wellness in positive and potentially negative ways. In this post we will look at how our use of screens, apps, and other tech tools affects our cognitive wellness.

In another research study of work habits, those who tried to respond to emails as soon as they came in - such as in the middle of a meeting about a different matter - rather than intentionally setting aside separate time to respond to emails actually lost 10 IQ points due to task switching. So, taken together, the research reveals the scary truth that when we attempt to multitask, we are actually harming our cognitive wellness.

While this is discouraging, we can apply this research to our habits to actually improve our focus and processing speed. For instance, create a classroom or workspace with limited distractions to help avoid task switching:

Once you make these strategies a part of your daily routine, you will find the ability to focus for longer time periods becomes easier, bit by bit. Flow and Languishing Screens tend to be our go-to distraction. They provide on demand content that tempts us to procrastinate. Despite this, it is possible for us to maximize our creativity and efficiency while avoiding the urge to put off certain tasks. To learn how, first we need to understand the concepts of FLOW and LANGUISHING. Flow is a term coined by researcher Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi in 1988. Flow is an ideal cognitive state we experience when we are completely concentrated on a task that is intrinsically rewarding, we feel in control, and time passes quickly. Screens can be a barrier to experiencing flow. While time tends to get away from us while we are staring at our screens, we do not step away feeling fulfilled or that we were in control. Languishing is a mental health term that has been around for a while, but has become more well known recently thanks to Adam Grant. He explains, “Languishing is the neglected middle child of mental health. It’s the void between depression and flourishing — the absence of well-being. You don’t have symptoms of mental illness, but you’re not the picture of mental health either. You’re not functioning at full capacity. Languishing dulls your motivation, disrupts your ability to focus, and triples the odds that you’ll cut back on work.” Often, we find ourselves on our screens when we are languishing. Avoiding work or other enjoyable cognitive tasks. The solution is to start noticing these habits in ourselves.

Once we are able to recognize our own tendencies we can talk about it with our partners, coworkers, and the children we serve. Our own awareness and modeling will help them develop self-awareness too. Next Steps Use the research and strategies I’ve shared here both in your home and in your classroom to improve your Cognitive Wellness. Then share what you’ve learned with your young learners. Just as they can build muscles, they can build strength and stamina in their own thinking and concentration with your help. I’m looking forward to seeing you back here soon. Our next Digital Wellness post will tackle our moods, feelings, and sense of self with Emotional Wellness. Check out other articles in this series: What is Digital Wellness, Physical Wellness and Emotional Wellness. By: Shaunna Harrington, Ph.D. MASCD President Associate Teaching Professor, Northeastern University @shaunna3830 Email Shaunna  It is National School Counseling Week and I want to take this opportunity to recognize the important role school counselors play in the Whole Child approach to education -- to ensuring that “each child, in each school, in each community is healthy, safe, engaged, supported and challenged.” School counselors are critical to the work of creating and sustaining equitable and inclusive schools. They have a unique perspective on what is going on in our schools because they work across the domains of academics, social-emotional development, and college and career readiness. Over the past 15 years, there has been a paradigm shift in how districts and schools envision the role of school counselors. In Massachusetts, this ongoing transformation has been led by the Massachusetts School Counselors Association (MASCA) through their Framework for Comprehensive School Counseling Programs (Model 3.0 was released in 2020). The vision guiding the Model is to move school counseling from a “reactive, crisis-based model that was the 20th century norm” to a “proactive, programmatic approach.” In this approach, school counselors provide Tier 1 supports, in addition to Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports, which means all students get to work with a school counselor. In schools using the Model, school counselors use data to identify issues impacting students, and play leadership roles in advocating for, and helping to implement, effective interventions. Now more than ever, as our children and adolescents continue to grow up and go to school during a global pandemic, our students need to be in schools with an adequate number of school counselors. The American School Counseling Association (ASCA) recommends a ratio of no more than 250 students for every 1 school counselor. In Massachusetts, the ratio is 307:1 (based on data from 2015-16). About 1 in 5 students in Massachusetts, nearly 200,000 students, do not have access to any school counselor, and 30% of high school students, about 84,000 students, are enrolled in a school where there is not a sufficient number of school counselors. It is important to recognize that school counselors are allocated inequitably across schools in the Commonwealth. EdTrust explains, “Massachusetts is shortchanging its students of color and students from low-income families, by providing fewer school counselors in schools with more of these students.” Several studies have shown there are positive impacts when school counselors work with a smaller caseload. Students from low-income families and students of color in particular benefit from having more access to school counselors. High-poverty schools that meet the recommended ratio have better outcomes for students, such as improved attendance, fewer disciplinary incidents, and higher graduation rates. Black students are more likely than their white peers to identify their school counselor as the person who had the most influence on their thinking about postsecondary education. Our students need more school counselors in Massachusetts and across the U.S. At the end of 2021, Massachusetts Representative Katherine Clark, along with Senator Jeff Merkely of Oregon, introduced the Elementary and Secondary School Counseling Act (H.R.6214), which would provide direct funding to states to lower the staffing ratios for school counselors, school psychologists and school social workers in order to “effectively staff the high-need public elementary schools and secondary schools of the United States with school-based mental health services providers”. The bill has not yet been voted on. Let’s use next week’s National School Counseling Week to focus on making changes that can increase the positive impact of school counseling for our students.

By: Shaunna Harrington, Ph.D. MASCD President Associate Teaching Professor, Northeastern University @shaunna3830 Email Shaunna

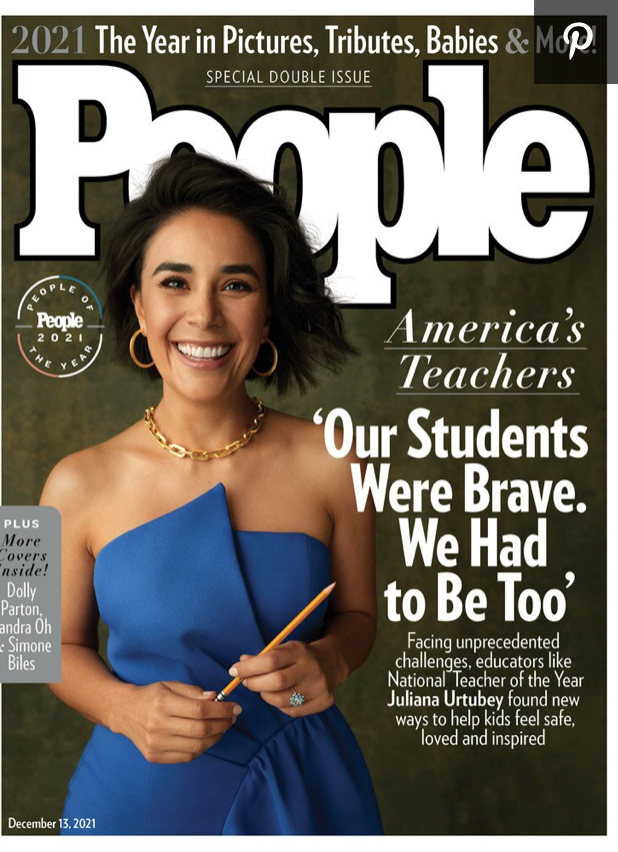

I love seeing teachers recognized and celebrated as the People of the Year! But I am also wary of superficial accolades that fail to lead to better conditions for teachers in the complex, challenging work they do each day. Many teachers have shared with me that this school year (2021-22) has felt harder than last year (2020-21). They don’t want to romanticize what it was like to teach remotely and to teach in a hybrid model, but they say last year social-emotional needs and relationships were prioritized, flexibility and generosity were valued, and new ideas and strategies were embraced – and that this year, much of that has been lost in the effort to quickly “get back to normal” and make up for “learning loss.”

We are back in school buildings now, but students are still struggling with the challenges of growing up and going to school during a pandemic. More than 140,000 children in the U.S. have lost a parent, a custodial grandparent, or grandparent caregiver to Covid-19. Educators are still struggling with how to meet the additional needs of their students while also having to deal with attacks on antiracist education, staffing shortages, and some community members who oppose masks and other public health safety measures. Large numbers of teachers are reporting that they feel burned out and demoralized. We need healthy teachers to support healthy growth in children, and that means our society needs to take seriously our investment in teacher well-being. Some of the most impactful steps are for schools to offer comprehensive mental health supports; reduce the extensive demands on teachers; and empower teachers in decision making. Teachers serve one of the most important roles in our society. Let’s shout that from every magazine cover and any other platform we have access to! And let’s keep pushing for policies that provide teachers with the supports they need to be able to continue to make their incredible and varied contributions to our kids and our communities.  By: Dr. Cathy Collins | @Dr_CathyCollins | [email protected] Dr. Cathy Collins is currently working as a Technology Teacher (Specialist) at Sharon Middle School.Dr. Collins served on the MassCUE Board as PD Chair from 2015-2019, and has published her writing in various journals including “EdWeek,” "English Journal," “Library Media Connection,” “NEA Today,” "eSchool News" and “Knowledge Quest.” She served on the MA State Science Ambassador Team, ISTE STEM PLN Leadership Team and Mass School Library Media Association as Advocacy Chair. She was elected this past November, 2020, to serve a three year term on the ISTE Board of Directors. Book Review: “The Future of Smart: How Our Education System Needs to Change to Help All Young People Thrive" I regularly teach my 7th grade students about the Engineering Design Process through a range of hands-on and technology based activities. I emphasize that there are many approaches to problem solving, and that improvement is always possible. As I think about the current challenges of education in America, and confront the daily news about chronic student absenteeism, teacher burnout and a host of other critical issues, I’m reminded that though the list is daunting, any one of us in this business of education at any level in the system does have the opportunity to help re-imagine, rebuild and redesign toward a more learner-centered vision for education. In the words of Peter DeWitt, Ed.D., “Anyone who gets into teaching needs to believe that they can improve the educational experience for their students.” In the words of poet Emily Dickinson, “Hope is the thing with feathers.”

In “The Future of Smart: How Our Education System Needs to Change to Help All Young People,” by Ulcca Joshi Hansen, PhD, JD, we are encouraged to imagine an education system grounded in a different world view that embraces and celebrates the individual nature of human development. She illuminates systemic challenges, provides historical context and analysis of how we landed here, and shines the light forward through a holistic, learner-centered approach in which our children’s humanity and uniqueness is truly nurtured. In this transformational model, the purpose of education becomes the nurturing and crafting of identity along with the discovery of abilities that empower all students to contribute to their own and their community’s well being. I recommend this book to any educator looking to reimagine how we can best serve our children and communities. It offers a breath of fresh air and an affirmation of the value of our work as we continue to confront current limitations and systemic inequities in our current, prevailing educational model. Dr. Hansen encourages an expanded definition of “smart,” beyond “an idea based on centuries of bias about what matters in people and cultures, and what doesn’t. This idea of smart is more than just a foundation for what we do in schools; it’s one of the organizing principles of our society. And it poses an existential threat to the development of our children and our communities.” She explores throughout the book what smart should mean and what our system of education should value most, starting with “the complexity of and richness of our humanity and the many different ways in which people engage with and contribute to the world.” Hansen highlights the opportunity in the present moment without sugarcoating the difficulties inherent in transformation. “The system is reluctant to allow radical change without a clear sense of what will replace the old ways. But 2020 forced us to abandon many of our default practices, and the resulting disruptions revealed how inadequate those practices have been all along.” She ends by challenging us to apply transformational ideas with a list of suggested action steps and the charge, “The choice is ours to make.”

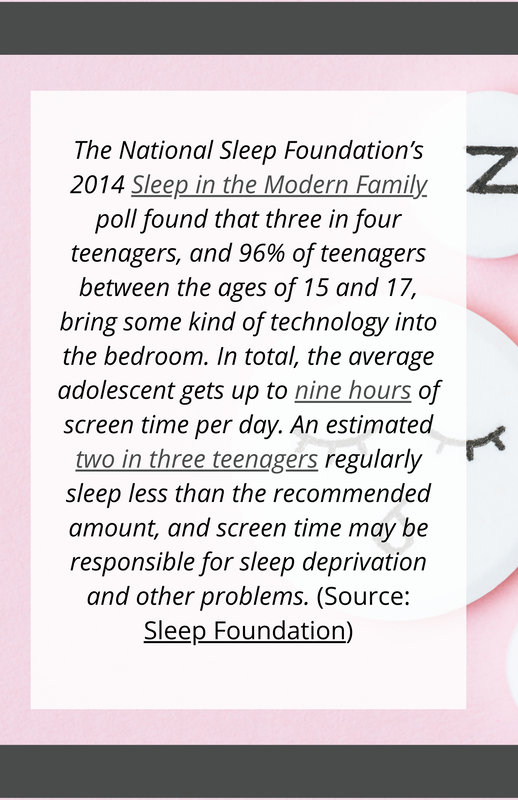

One factor is blue light. It is available to us through sunlight and also through the screens we use throughout the day: smartphones, tablets, flatscreen TVs, and laptops. Blue light sends a signal to our brains that it is daytime and we should be active. Eliminating blue light can help signal to our brains to get ready for sleep. There are a few strategies to help with blue light exposure: using blue light blocking glasses or adjusting blue light settings on the devices used close to bedtime. So it is possible to use technology and get great sleep. We just need to be strategic about it. Exercise Just like sleep and screens, a common misconception is that technology and exercise are mutually exclusive. The stereotypical adolescent on a screen is in a dark room with eyes wide staring at the beam of light washing over his face, and planted next to him is a pile of junk food. Surely you can picture it in your mind. In reality, this is not how most families are allowing their children to engage with screens. In fact, there are ways to encourage children to use technology to promote physical activity. Here are some examples: Recently, my middle school-aged daughter tried out for and made a competitive sports team. This new team comes with expectations that athletes will practice at home, not just at designated team practice times. The coach sent home video demonstrations of drills that she wants athletes to do. My daughter spends many afternoons (or evenings after dark with the floodlights on) in the yard watching the videos and practicing the drills because she knows her coach will hold her accountable for improving her skills. During the pandemic, my elementary school-aged daughter engaged in physical education workouts via video clips shared by her teacher. She cleared out the living room and learned how to plank! Since then, on days when she doesn’t have an after school activity, I sometimes find her looking up workouts or dances on YouTube. She is motivated to learn how to move to her favorite songs and enjoys it because she knows that moving her body makes her feel good after a long school day. When she makes this choice, we celebrate it to encourage her. Here are even more ideas to promote physical activity that are combined with screen use with children even younger than elementary age. Eye Health The medical terminology for some of the symptoms we often associate with screen use – redness, itching, dryness, headache, halos, and double vision – is computer eye syndrome. Around half of parents of middle and high school aged students reported these symptoms during 2020 while our K through 12 learners were on screens for academic purposes more than ever before. Of course, it is important to remember that screens were not just being used for school. Our children used screens during this time to stay connected to family and friends, to pass the time with games and social media, and for entertainment with streaming content. Let’s be honest: they still use screens for all of these purposes.There are strategies to help mitigate these symptoms while allowing our learners to benefit from the resources, creation tools, and collaboration possibilities available through their screens. For instance, remind the children you serve to reduce the brightness a bit to only what is needed. The positioning of the screen should be even with eyes or a bit lower than eye level so lids can cover and moisten the eyes during screen use. Finally, children who are enjoying a movie or game are less likely to take breaks. Before they start those activities, make a plan for them to take eye breaks by working with them to set timers or schedule a meal or screen-free activity that will happen after 30-45 minutes. In the classroom Teachers and school leaders can proactively create classroom routines and talk about strategies like these with students and parents. Just as we plan for students to practice their mathematics skills, reading skills, and collaboration skills, we should plan intentionally for students to practice being physically healthy while benefiting from the features and programs provided by technology. I’m looking forward to seeing you back here soon. Our next Digital Wellness post will tackle the risks, benefits and strategies associated with Cognitive Health while using technology. Check out other articles in this series: What is Digital Wellness, Cognitive Wellness

and Emotional Wellnesswww.mascd.org/blog/digital-wellness-is-emotional-wellness.  By: Kerry Gallagher @KerryHawk02 on Instagram & Twitter | www.KerryHawk02.com [email protected] Kerry is the Assistant Principal for Teaching and Learning at St. John’s Prep in Danvers, Massachusetts. She’s also the Director of K-12 Education for ConnectSafely.org – internet safety non-profit in Palo Alto, California.  Educators are surely familiar with the term “digital citizenship.” We are familiar with coaching and modeling for our students the ways toward acting as an upstander, blocking and reporting bullies and bad actors, and making the internet a more positive and truthful place. There is so much more to a healthy digital life than digital citizenship. I like to call this concept DIGITAL WELLNESS and our students and their families are hungry to learn about all of the ways they can develop better habits for technology use. In fact, 54% of U.S. teens think they spend too much time on their smartphones. Even their parents are eager for some guidance. Pew Research Center reports that 33% of American adults tried to cut down on internet or smartphone time at some point in the last 18 months. Parents and teens alike admit to struggling with distraction and focus when using their screens and researchers are still working to determine whether there is a correlation between screen time and likelihood of anxiety or depression. So, while digital citizenship and cyberbullying prevention are worthy topics for schools to cover, there is more ground to cover when determining a strategy for promoting positive healthy uses of technology and mitigating those unhealthy habits. So, what exactly is DIGITAL WELLNESS? A school culture of digital wellness certainly includes discussions of good citizenship, and it also encourages members of the community to consider technological and digital influences on other areas of overall digital health including:

In the coming months, we will examine each of these areas of digital wellness in more depth via a series of blog posts, social media posts, and video/audio podcasts. We will dig into research and ask you, fellow educators, to share your stories and experiences so that we can build healthy schools and classrooms together. The past 2 years have forced us to go through a transition of how we use and rely on powerful technologies. Let’s embark on a journey to fulfill the promise of using these tools for the benefit of our school communities while also promoting digital wellness. Continue this series by learning more about Physical Wellness, Cognitive Wellness and Emotional Wellness. Harper Lee Who? A Call to Replace Problematic Classics with Diverse Literature in Secondary Curricula by Cody Marx @codymmarx  During a recent session of school-sanctioned professional development, my colleagues and I scrutinized our current reading lists, one of which includes Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. In a general consideration of the work, many teachers throughout the nation are quick to justify teaching the novel to students year after year; some foster a sense of sentimentality for a story with which they interacted as students decades prior, while others praise the anti-racist message they’re able to draw from its themes. But in questioning the lack of diverse perspectives in the novel, in addition to Lee’s less obvious racist writing practices, I can’t help but wonder: If we want to discuss racism and anti-racist work in our classrooms, why aren’t our students reading works by writers of color? Are we sticking with Mockingbird solely because of a nonsensical dedication to tradition? Is that why Lee’s “classic” has remained a hallmark of high school English classrooms since its 1960 publication? Though the novel has remained secure on its pedestal in English language arts classrooms for six decades, the debate of Mockingbird’s place in education is not a new one. While educators and readers alike often praise the piece for its sensitive handling of racism, those working with an antiracist lens see more than a white man who risks his family’s safety and reputation to seek justice for an innocent Black man. Academics have time and again questioned the merits of a white author’s ability to accurately portray the realities of the American south during Jim Crow, and two such scholars stand out in their criticism of the work. Naa Baako Ako-Adjei (2017) minces no words in asserting that though Mockingbird is couched in a nostalgic coming-of-age story, its crowning achievement is its reimagining of “American history, as something far more benign than its reality” (p. 185). She contends that a number of Lee’s problematic choices - including a correlation between racism and poverty, the depiction of mild-mannered lynching mobs, and the minimization of the KKK - are designed to convince audiences of white innocence in spite of the omitted realities of racism during Jim Crow. Jennifer Murray’s (2010) work is similar to that of Ako-Adjei in that she, too, reads Mockingbird with a focus on the discrepancies between how Lee and a writer of color would have considered the same material. Murray notes that though Calpurnia, a Black servant whose identity is not rounded out with so much as a surname, is considered to be a member of the white Finch family - much like enslaved people were often designated as members of an enslaver’s family - Lee fails to include the cook in scenes other than those in which her usefulness to the family is obvious. Such observations, among several others, serve to distort the illusion of the work as anything other than an effort to unashamedly exonerate America of its racist history, a feat that only a biased white writer would attempt with this subject matter. But Harper Lee is far from the only mainstay of American literature whose work grows increasingly problematic as readers continue bringing their issues - racist and otherwise - to the light of modern consideration. Sonya Freeman Loftis (2015) criticizes John Steinbeck’s treatment of neurodivergence in his 1937 novella Of Mice and Men, explaining that Lennie, one of the two protagonists, is a cognitively disabled man prone to fits of violence who is only depicted in relation to George, his neurotypical counterpart. This portrayal, combined with Steinbeck’s description of a character with undeniable qualities of someone on the autism spectrum, allows readers to form beliefs of people with autism that are both false and dangerous. Similarly problematic is another beloved staple of American literature: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850), the telling of a woman’s journey through public shame after committing adultery. Though Hester Prynne is often praised as a feminist rebelling against the Puritanical patriarchy, the novel’s heavily biased narrator continuously uses Hester’s existence as a spurned lover to paint her as a victim who is incapable of rising to true rebellion (Leverenz, 1983). Furthermore, Hawthorne shies away from committing to the destruction of societal conventions as Hester rejects conflict upon becoming a mother, an apparent cure-all for any radical independence. In many cases, these are the only types of books that our students are reading, and we wonder why they aren’t enthralled by literature. Schools have continued to peddle works by writers who have little to no business addressing the perspectives and themes they do, which has typically resulted in the presentation of diverse groups of people as less than fully human. Addressing this failure is part of our job as educators (Thomas, 2016). And make no mistake: the inaccurate representation - or complete erasure - of diverse characters is a true failure. The actual incorporation of diverse literature works wonders in the education of children. Bishop (2012) asserts that children who are typically absent from children’s literature begin to demonstrate greater self-esteem when seeing themselves represented textually, while Thomas (2016) even alleges that these efforts to diversify literature will “begin the work of healing our nation and world through humanizing stories” (p. 115).

At New Bedford High School, the English language arts department, led by content instructional leader Jennifer Oliveira, is already well into work in diversifying curricula that once focused heavily on white voices. Having understood the importance of reading representative literature in classes where more than two-thirds of students are people of color, the NBHS ELA department has spent the 2020-2021 school year incorporating novels with perspectives from people of color, like Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down, Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give, and Nic Stone’s Dear Martin, to balance out the tired narratives of writers like Lee, Steinbeck, Hawthorne, and more. With a determined focus on continuing to improve representation within department curricula, Oliveira recognizes that the inclusion of Black writers is not enough, which is why she’s convened a committee of teachers to expand their inclusive efforts to female, queer, genderqueer, disabled, neurodivergent, Latinx, Asian, Middle Eastern, Native American, and indigenous perspectives. It is her hope that the upcoming 2021-2022 school year will find students engaging with the stories of Benjamin Alire Sáenz (Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe), Sandra Cisneros (The House on Mango Street), and Khaled Hosseini (The Kite Runner), along with others like Julia Alvarez, Toni Morrison, Malala Yousafzai, and Sherman Alexie, all of whom can better expose our students to the belief that their unique perspectives are valid and belong in the classrooms we share and in the stories we tell. Cody Marx is a high school English language arts teacher in Massachusetts. |

Guest AuthorContact us at [email protected] to write for our organization! Categories |

Photo from Mike Kniec

RSS Feed

RSS Feed